The Settlement House Movement

After the Civil War, the emancipation of slaves, influx of immigrants, and industrialization spurred more activism in social work. Around the turn of the 1900s, northern cities experienced an influx of immigrants from Europe and a Great Migration of African Americans from the American South. Between the 1880s and 1920s, hundreds of settlement houses were established in American cities in response to European immigration and urban poverty brought about by industrialization and exploitative labor practices. Settlement houses provided support services like education, healthcare, childcare, employment resources, and even offered kindergarten classes before they were offered in many public school districts.

Many middle-class charity workers thought that poverty was a moral failing. Charities often lumped people into categories of “worthy” or “unworthy” of help. The settlement movement changed popular conceptions about charity and social welfare. They approached the poor from a different perspective, and envisioned not charitable work, but social work.

Toynbee Hall opened in London in 1884, and was the prototype for the settlement house. Stanton Coit lived there for several months, and was inspired by it to open “Neighborhood Guild” in 1886, the first American settlement house on the Lower East Side of New York. In 1889, Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr launched Hull House in Chicago. The Hull House served as a model for over 400 other settlements across the country.

Addams explained that those with public spirit could use their knowledge of tenants’ rights to help and cooperate with immigrants living in crowded unsanitary tenements who did not know how to reach the board of health. Addams believed in the interdependence of social classes and in the importance of working with and among working class communities. As settlement house residents learned more about their communities, they proposed changes in local government and lobbied for state and federal legislation on social and economic problems.

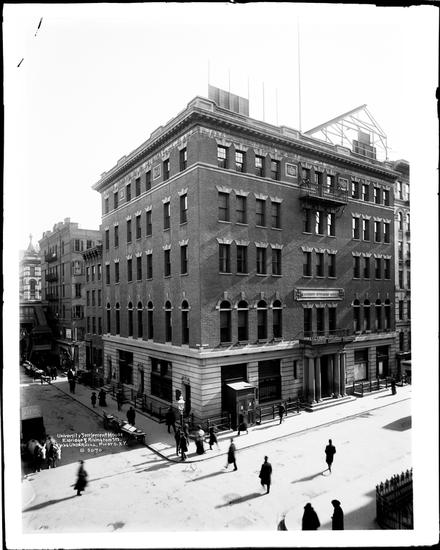

Lillian Wald was a nurse who taught lessons in a school in the Lower East Side, New York. When she learned of the unsanitary conditions in tenements and the poor health of their inhabitants, she became determined to move to the neighborhood, to live among the poor. With fellow nurse Mary Brewster, she rented an apartment as a place to provide health care to the community, and eventually moved the settlement to a house purchased for her by philanthropist Jacob Schiff. Founded in 1893, this became the Henry Street Settlement.

Jane Addams and Lillian Wald also campaigned against child labor and for public health, sanitation, industrial workplace safety reform, and women’s suffrage. Many settlement houses established during this period are still thriving today.

During the Great Migration, many white-run settlements and other institutions, like the YWCA, refused to serve African Americans. Others served Black families when they lived nearby, but did not do outreach into Black neighborhoods. African American activists, including Ida B. Wells and Elizabeth Lindsay Davis, were the driving forces behind expanding African Americans’ access to social services. These reformers created separate or integrated facilities in African American neighborhoods to help Black migrants adjust from life in the rural South.

Current or former settlement workers helped craft the Social Security Act of 1935 and other reform legislation of Franklin Roosevelt’s administration. The War on Poverty in the 1960s would revive many settlements that closed due to the Great Depression. In 1966 the settlement’s budget was about $100,000, mostly from private sources, but by 2002 its budget was $33,000,000, with 80 percent coming from government sources.

Today, the settlement house remains one of the primary community-based social-service providers in NYC. Places called “neighborhood house,” “settlement house,” and “community center” are often part of the settlement-house tradition. Settlements today are different from those founded in the 1890s and 1900s—they no longer have workers living as residents, they receive more public than private funding, and they no longer see creating cross-class relationships as central to their mission—but they still reflect the initiative of the settlement-house founders to provide direct services to communities in need.

Learn More

Gibson, Samantha. “Settlement Houses in the Progressive Era.” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/settlement-houses-in-the-progressive-era. Accessed 24 Mar. 2023.

“Hull-House · National History Day: Revolution, Reaction, Reform in History.” Jane Addams Digital Edition, https://digital.janeaddams.ramapo.edu/exhibits/show/nhd-rrr/revolution/rrr-hull-house. Accessed 25 Mar. 2023.

Nunez, Ralph da Costa, and Ethan G. Sribnick. “Settlement Houses in New York: From Past to Present.” The Gotham Center for New York City History, 17 July 2013, https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/settlement-houses-in-new-york-from-past-to-present.

Ryerson, Jade. “Settlement Houses in Chicago.” National Parks Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/settlement-houses-in-chicago.htm. Accessed 25 Mar. 2023.

Wade, Louise Carroll. “Settlement Houses.” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1135.html. Accessed 24 Mar. 2023.