3 Eugenics and Psychology

As an editorial note, throughout this chapter we will encounter descriptions of people from the perspective of eugenics. For example, eugenics differentiated people on the basis of human characteristics that eugenicists decided were desirable or undesirable. As a result, people who had eugenically desired traits were labelled as “high-quality” or “superior” compared to people who had eugenically undesired traits, who were labelled as “low-quality” or “inferior”. These and other similar descriptors of human beings will sometimes be used in this chapter for the purpose of describing dehumanizing aspects of eugenics ideology.

3.1 Eugenics, psychology and the cognitive sciences

If you are interested in learning more about a critical history of psychology, I highly recommend Guthrie (2004)’s “Even the rat was white: A historical view of psychology”, first published in 1976.

Including a chapter about eugenics is not very common in introductory psychology textbooks (but see, Guthrie, 2004). When I learned about histories of psychology and cognitive psychology the topic of eugenics was rarely discussed. One reason for the lack of coverage might be that cognitive psychology and the cognitive sciences became established academic disciplines well after the primary eugenics movements had come and gone; and, eugenics may be viewed as “ancient history” or irrelevant to discussions of modern day cognitive sciences. However, the rise and gradual fall of the eugenics movement is inextricably intertwined with psychology, especially around the turn of the 20th century and even into the 1950s (Yakushko, 2019). Although the modern cognitive sciences were established between the 1950s and 1980s, research into cognitive abilities had been ongoing for decades prior to the so-called “cognitive revolution”. The eugenics movement substantially influenced early branches of research into cognitive abilities, and shaped the kinds of questions, tools and methods, and applications that the research enterprise held for society.

What was the eugenics movement? How did it get started, what did it do, when did it end? How was psychology involved? And what does eugenics have to do with cognition? These questions are explored across chapter three and four.

3.2 Eugenics: an overview

Last chapter we learned that Sir Francis Galton was interested in mental abilities because of his research into individual differences in the vividness of mental imagery. However, throughout the chapter I did not elaborate on the fact that Galton was also interested in eugenics, which motivated him to conduct the research in the first place.

Here is a brief overview of eugenics. Galton began publishing articles that were formative to eugenics as early as 1865 (Galton, 1865). Eugenics transitioned from ideas about “improving society” in journal pages read by small groups of academic elites, into a large and complex social movement that was broadly accepted– from everyday citizens to national leaders– in numerous countries around the world (Kühl, 2013) up until the 1940s and 50s.

A basic idea in eugenics was that society could be improved and its problems solved by selectively breeding humans, just like other animals. Eugenicists assumed that traits they considered desirable, like human “intelligence,” were inherited from parents. They argued that society as a whole could become more intelligent over generations by breeding intelligent people with each other. Similarly, eugenicists assumed that traits they considered undesirable, like “feeble-mindedness” 1, were inherited from parents; and they argued that society as a whole could eliminate undesirable traits over generations by preventing people deemed undesirable from having offspring.

The eugenics movement established itself in many countries and sought to enact social policies to further the aims of the eugenics movement. Their policies were responsible for many human rights violations and atrocities. The remnants of eugenics campaigns have left lasting impacts on society that continue today.

This chapter is not intended to provide an exhaustive history of eugenics. If you are interested in learning more about the topic consider reading the books and articles cited in this chapter. Also, I maintain a eugenics reading list with many more additional reading suggestions.

The early discipline of psychology was complicit in eugenics and large numbers of psychologists were eugenicists (Yakushko, 2019). The general involvement of psychology reflects the widespread acceptance of eugenics in society (psychology wasn’t special in this regard). It was the specific aspects of psychology’s involvement that warrants the descriptor “complicit”.

The eugenics movement needed ways to “scientifically” measure physical and mental qualities of individual people. Psychologists helped create and deploy the tests of human ability (e.g., intelligence tests, see next chapter) that would be used to carry out eugenics campaigns on society. Research concerned with cognitive abilities was motivated and deeply entrenched in eugenics for well over half a century (1900s-1950s). The cognitive sciences did not emerge unscathed from this historical backdrop while advancing attempts to explain how cognitive abilities work, and connections to cognitive science are mentioned in upcoming chapters.

3.3 Galton’s Eugenics

Eugenics was a potent mix of ideas ranging from scientific claims, social policy, religion, and visions of Utopia. Although eugenics ideology morphed over time and geographical place (Bashford & Levine, 2010), the basic tenets of the movement are still captured well by Galton’s early writings. In 1865, Galton wrote “Hereditary talent and character” (Galton, 1865), a short paper that was expanded to a book a few years later, “Hereditary Genius” (Galton, 1869). These works describe Galton’s ideas about human quality– that some humans are much more superior in quality than others– his research claiming that the most important human qualities are hereditary (biologically inherited from parents), his fears that society was degrading all around him, and his plan to save society by creating a new scientific religion capable of engineering a supreme human race over generations, simply by controlling human reproduction.

Galton referenced the practice of dog breeding, which involves selectively mating dogs with particular physical and behavioral traits over generations of broods. Dog-breeding was a choice example, because it would have been obvious to anyone that breeding over generations can produce dramatic results: all of the many different dog breeds have been achieved through breeding. One of Galton’s radical claims for the time, was that breeding should be used on humans, just like dogs, and that breeding programs would be a simple, straightforward, and already well-understood method to produce a superior race of humans over generations.

Galton’s eugenics ideas did not appear in a vacuum, and they were influenced by the scientific and social context he was working in. Galton’s eugenics writings appeared just after Charles Darwin (his cousin) published the theory of evolution in the Origin of the species (Darwin, 1859). Darwin’s theory explained how animal species evolved over time through a process of natural selection and remains a powerful explanation of life on earth. This same time period included threats to British imperialism and efforts by many nations to establish their dominance and socio-cultural order across the globe. Galton was an esteemed upper-class British man of science (eventually knighted in 1909), who held sexist and racist views common among his peers. For example, long before genetics would show that there is no biological basis for race (Yudell et al., 2016), academics like Galton assumed that people from so-called “uncivilized” countries were of much lower quality than people from “civilized” countries, and that these differences must have evolved, and must be heritable. Furthermore, in the tradition of Thomas Malthus – who is famous for speculating about the imminent collapse of society as a result of population growth– Galton feared that society would deteriorate over the generations due to increased global interactions between people across the world. Specifically, Galton feared that “natural selection” left to chance would allow inferior, low-quality and uncivilized people to reproduce, pollute the gene pool, spread undesirable genes across the world, and cause the slow decline and ultimate destruction of the human race.

Galton saw eugenics as a way to wrest his vision for human destiny from natural selection, and use the new powers of science and technology to save humanity from itself. Eugenics was not just concerned with improving society for one generation; it would be marketed as a quasi-religious movement dedicated to enhancing humanity across generations, for the rest of time. Although improving humanity might not seem like a frightening goal, it is worth considering questions like: What is being improved? Who gets to decide what needs improving? What changes count as improvement? Who will benefit from the improvement? Will the costs of improvement be shared equally? In answering these questions, the eugenics movement argued that improving humanity meant identifying and eliminating eugenically low quality humans from the species; which is a frightening prospect for large groups of people who were dehumanized by eugenicists.

3.4 The Eugenics movement

Galton’s eugenics ideas could have stayed on the page, like most dystopian science fiction novels, but unfortunately they took on a life of their own. In this section, the scale of eugenics is established by examining its dimensions as a social movement.

Utopias and science-inspired visions for more perfect societies are discussed in more detail in chapter 6. As a point of interest, Galton also wrote a utopian novel titled, “The Eugenic College of Kantsaywhere” (Galton, 1910).

3.4.1 A Timeline

The eugenics movement spread from Britain around the world and impacted different countries in similar and unique ways. For a very informative timeline on major events in the eugenics movement take a look at the interactive timeline created by the Canadian-funded eugenics archive project. Although the timeline includes many events relevant to Canada’s eugenics legacy, it also provides comprehensive coverage of important historical events in eugenics movements worldwide.

3.4.2 From ideas to internationalization

Galton continued to expand and popularize his ideas and coined the term “eugenics” in 1883 (Galton, 1883). In these few decades, eugenics proponents succeeded in blaming an array of social problems on diverse groups of people labeled as undesirable and inferior, based on characteristics like skin color, ethnicity, and mental illness or disability. Furthermore, eugenicists argued that these undesirable characteristics were heritable traits. Eugenics promoted fears that hordes of undesirable people were breeding and spreading their undesirable traits throughout society; and, that society would ultimately degenerate and collapse unless actions proposed by eugenicists were taken to save society.

By 1882, eugenic fear spread to American immigration policy, and immigrants who were found to be “undesirable” could be denied entry to the USA (Baynton, 2005; Chen, 2015). By 1897, fear that “degenerates” would reproduce and overwhelm society led lawmakers in Michigan to propose a compulsory sterilization law – allowing the state to forcibly sterilize any woman deemed to be a degenerate. Compulsory sterilization laws were adopted by over 30 states and led to 60,000 forced sterilizations (Eugenics, n.d.).

By the early 1900s formal eugenics societies were being established around the world. In Britain, Galton sat as the first president of the Eugenics Education Society in 1907. One year earlier, Charles Davenport formed a Eugenics committee inside the American Breeders Association– a pre-cursor to the Eugenics Record Office, which was the national headquarters of eugenics in the USA (located at Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory in Huntington, Long Island, NY) (Allen, 1986). Eugenics societies spread across the world. The Oxford handbook of the history of eugenics (Bashford & Levine, 2010), has individual chapters describing the aftermath of eugenics in Britain, South Asia, Australia and New Zealand, China and Hong Kong, South Africa, Colonial Kenya, Germany, France, the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies, the Scandinavian States, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, Russia and the Soviet Union, Japan, Iran, the Jewish Diaspora; Cuba Puerto, Rico, and Mexico; Brazil, the United States, and Canada.

3.4.3 Conferences and popularity

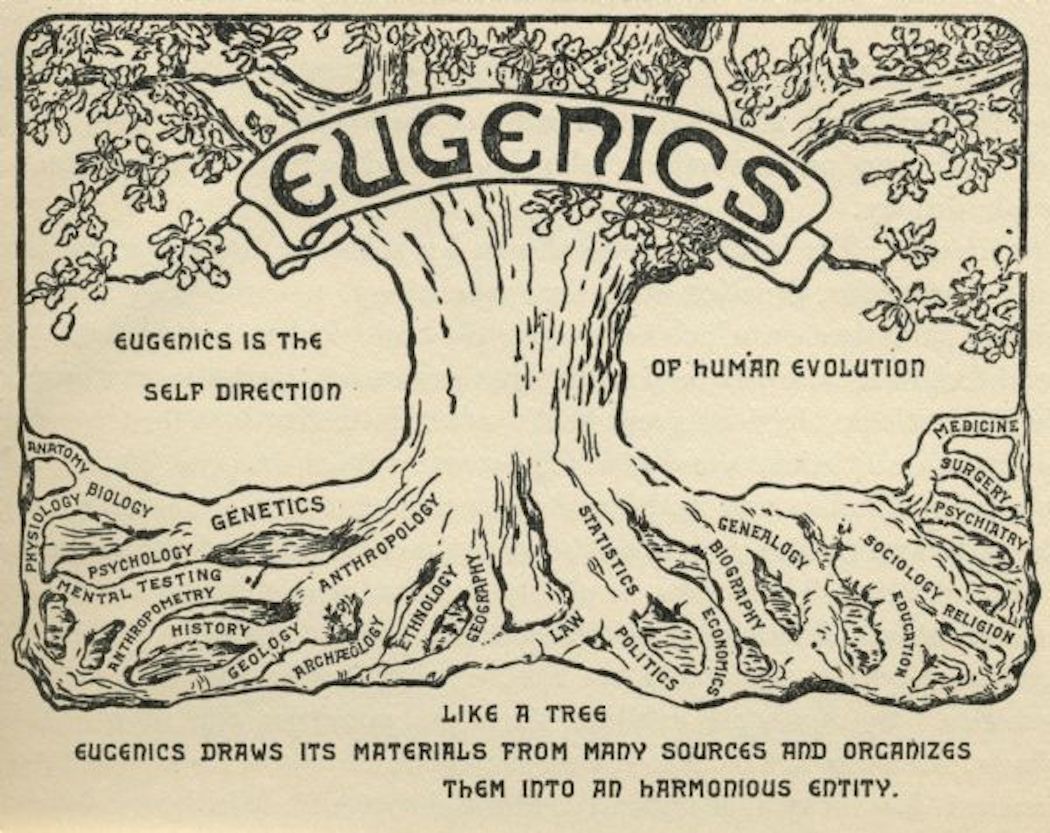

There were many national and international conferences where elites in the eugenics movement gathered to popularize and discuss eugenic solutions to improve society. For example, the first national conference on race betterment was held in Battle Creek Michigan in 1914 2. The first (1912), second (1921) and third (1932) International Eugenics Congresses were held in London, and New York (last two). The tree of eugenics in Figure 1 was created for the second conference and depicts how the movement saw itself as, “the self-direction of human evolution”, that would harmoniously integrate many fields of study for the purpose of bettering mankind. Just like each of the countries listed at the end of the last section, the academic fields listed in the roots of the tree of eugenics each have their own eugenics legacies to contend with.

In America, eugenics appealed to large segments of society and was embraced by celebrities, national leaders, and everyday people across the country. Some famous Americans who were strong proponents of eugenics include Alexander Graham Bell (inventor of the telephone), John Harvey Kellogg (Kellogg’s Corn Flakes), and Theodore Roosevelt (American President). During the height of its activity, the Eugenics Record Office trained scores of operators to disseminate information about eugenics across the states. For example, it would be common to attend a county fair and learn about eugenics at a eugenics information tent. Or, to participate in eugenics contests, like the “better babies” contests, where families had their babies judged to win the prize for highest quality baby (by eugenical standards) (Selden, 2005). The take-home message here is that the eugenics movement was highly organized and its proposals for improving society were very well known, commonly accepted, and fanatically embraced by its strongest adherents.

3.4.4 Eugenics Journals

As the tree of eugenics shows, the movement thought of itself as the culmination of many academic disciplines. Although eugenics did not succeed in perpetuating itself as a new academic department in universities across the world, it claimed to be a science for many years and it did establish academic journals and related publications. A few English language eugenics journals include: The Eugenics Review, The Eugenical News 3, The Journal of Race Development (whose first editor was the first president of the American Psychological Association, Granville Stanley Hall), and the Annals of Eugenics (which was renamed Annals of Human Genetics).

Eugenics journals allow unusual access to the history of the movement because the development of eugenical ideology, and its claims and methods for influencing society are all written down in the journals, books, conference proceedings, and other propaganda (including textbooks, pamphlets, and movies) produced by the movement. Some of the above eugenics journals stopped publishing, and others renamed themselves (and continue to publish) after the eugenics movement became socially unacceptable. Even though the eugenics movement has been widely discredited as pseudo-scientific nonsense, adherents of the movement have continued to promote their ideas even up to the present day.

3.4.5 Eugenics Fears

Fear of people on the margins of society was a common feature of eugenics movements across countries. Fear was created in two ways. First, fear was created by sub-humanizing already marginalized groups of people, labeling them as mentally and physically inferior, and using descriptors like, degenerate, impure, and moral monsters, to underline the message. Many different groups of people were targeted by eugenics and deemed unfit: from people with physical and mental disabilities, to immigrants, and people with different colored skin from the dominant eugenics movement in a particular country. In majority white countries like Britain, Germany, Canada, Australia, and the United States, the eugenics movement forwarded an agenda of white supremacy and reinforced existing forms of racism against non-whites. Non-white citizens were deemed inferior, and a common strategy was to fabricate scientific evidence showing that white people were superior in terms of eugenically desired traits (like intelligence) compared to non-whites.

Second, eugenicists suggested that marginalized groups of people would cause the collapse of society. The following characterization of “eugenics logic” is similar to what you might read in eugenics propaganda: “Inferior people are inferior because they have inferior genes. Inferior people pass on their inferior genes to their offspring when they have children, and they create inferior children with inferior genes. Also, many disgusting and inferior moral degenerates reproduce at very high rates. Society is deteriorating as we speak because so many inferior people are breeding, and society as we know it will collapse unless we follow eugenics solutions to the problem.”

3.4.6 Positive and Negative Eugenics

Eugenics promised scientific solutions to the problems it identified in society, and presented itself as a progressive social movement. Eugenicists distinguished between positive and negative eugenics as two general directions that would help improve the human race across generations through breeding.

Positive eugenics were ostensibly methods that would increase or encourage reproduction between high quality people (as determined by eugenics values). Negative eugenics involved methods for decreasing reproduction between low quality people (as determined by eugenics values). In practice, eugenics methods increased existing inequalities in society– positive eugenic methods gave more privileges to already powerful and privileged groups, and negative eugenic methods took away privileges (and much worse) from already marginalized groups. Wide-ranging positive and negative eugenics policies were deliberately deployed in many countries for many decades, and remnants of these policies continue to influence modern society in many ways. The following quote from Galton (1883) was prescient in describing the variety of strategies eugenicists would adopt to influence society with their social policies.

“a brief word to express the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognizance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give to the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had (Galton, 1883, p.17)”

The next section lists some of the eugenics policies that had lasting impacts on society.

3.5 Influences on society

Because eugenics was so widespread and common in many countries for a very long time, it had the opportunity to influence society in numerous and sometimes unexpected ways. Here is a short list.

3.5.1 Eugenics and Mental health

Eugenics ideology shaped the history of mental health treatment (Dowbiggin, 1997; Fischer, 2012; Thomson, 2010). People with mental illness were treated as genetically inferior. Negative eugenics was used to prevent people with mental illness from reproducing. One strategy was to institutionalize patients in mental hospitals that were in distant locations, which would physically isolate people and prevent them from breeding with the general public. Another strategy was to forcibly sterilize patients against their will to ensure they could never reproduce. For example, the United States passed compulsory sterilization laws for “defectives” in over 30 states.

3.5.2 Eugenics and Racism

Eugenics reinforced existing forms of racism in several ways. White eugenicists were concerned that the “white race” would degenerate if it mixed with “inferior” non-white races. In America, eugenicists supported increased segregation between whites and blacks, which would limit inter-marriage; and, they supported miscegenation laws to make inter-marriage illegal (Lombardo, 1987).

3.5.3 Eugenics and Fertility control

Eugenics was highly concerned with fertility control issues. As a result, eugenics overlapped with other progressive movements, such as the women’s movement to legalize abortion. For example, Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, was also a eugenicist. Abortion would be a welcome tool for eugenics because it could be used to terminate pregnancies resulting in eugenically “defective” or inferior offspring. Margaret Sanger, like other eugenicists at the time in America, was also involved in the white supremacy movement, and promoted her views by giving talks to white supremacy groups. Many modern institutions and organizations have eugenic legacies in their past, and it is notable that Planned Parenthood has begun publicly acknowledging and reckoning with this history (Johnson, 2021; Parenthood, 2020).

3.5.4 Eugenics and Education

Eugenics was involved in American education in numerous and sometimes unexpected ways. Eugenicists spread their views in schools through textbooks, such as high school biology textbooks, that reinforced eugenics beliefs and ideas (Selden, 1999). Gifted school programs were born out of positive eugenics to develop eugenically “superior” children (Mansfield, 2015), and concerns about racial bias for admission to these programs remain current 4. Standardized testing in education was created and proliferated by psychologists who were committed to the cause of eugenics, such as Carl Brigham a psychologist and eugenicist who was hired by the College Board to create the SAT. Edward Thorndike, sometimes lauded as the father of educational psychology, was a prominent eugenicist who wanted to use education for purposes of eugenics. Even the playground movement, which advocated for schools to include playgrounds, was mired in eugenics (Mobily, 2018).

An example of the continuing trauma from eugenics policies in education (Chapman, 2012) comes from Canada’s residential school system. These schools were in mandatory operation from 1894 to 1947, and the last one closed in 1996. In this boarding school system, indigenous children were separated from their parents to assimilate them into Canadian culture. Eugenics policies included the practices of segregation and institutionalization (by sending the children to remote locations); and, many indigenous female students were involuntary sterilized (Pegoraro, 2015). Child abuse was rampant. In 2021, the remains of children in unmarked gravesites were discovered on the grounds of several residential schools across Canada, with victims numbering in the thousands. The Canadian government is attempting reconciliation for survivors, families, and communities affected by the residential school system through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

3.5.5 Eugenics and Genocide

One of the most notorious outcomes of the eugenics movement occurred in Germany during world war II. Just as America had its eugenics societies, like the Human Betterment Foundation, Germany’s eugenic movement established itself beginning in 1905 as “Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rassenhygiene”, or the “German Society for Racial Hygiene”. Their eugenic goals included creating a purified and superior white race, and those goals were acted upon by committing atrocities like the holocaust.

The precursors of the Nazi eugenics program were already well-established by eugenicists in other countries. For example, the English statistician Karl Pearson (the inventor of Pearson’s correlation coefficient) was Galton’s protege, and became the first “Galton Chair in National Eugenics” at the University College London after Galton’s death in 1911. Pearson used his statistics research for eugenics. To take one example, Pearson established the journal “Annals of Eugenics” in 1925, and published a series of four lengthy (approximately 400-500 pages in total) research papers that demonstrated how to “scientifically” measure Jewish children and their parents to identify eugenically inferior Jews, so that the “cold light of statistical inquiry” could be used ultimately to stop Jewish immigration to Britain (Pearson & Moul, 1925). The Nazi regime would elaborate on these publicized methods and take them to their extreme conclusion, which included the genocide of an estimated six million Jews in the holocaust, and mass killing of other groups deemed to be eugenically inferior such as homosexuals, and mentally disabled people.

The numerous Nazi war atrocities which were clearly driven by and connected to the German eugenics movement are commonly cited as a reason for the world-wide decline of the eugenics movement after world war II. In America, the previously very public eugenics movement became unpopular. Eugenics journals changed their names. Eugenics societies stopped publishing their member lists. The damaging legacy and history of eugenics movements continues to the present day, and additional coverage is beyond the scope of this chapter. For further reading on this topic consider these books (Bashford & Levine, 2010; Kühl, 2013; Wilson, 2018).

3.6 Psychology and Eugenics

The aim of the preceding sections was to convey ideologies of eugenics, the tremendous scale and acceptance of eugenics across the world for at least half a century, and some of the fallout from the movement. The next section reviews connections between psychology and eugenics, which provides context for the next chapter on mental testing.

3.6.1 Emergence of Psychology

In 1879, the first experimental psychology lab was established by Wilhelm Wundt in Leipzig, Germany. The first psychology department in the United States was established by Granville Stanley Hall at Johns Hopkins University in 1883. Psychology spread quickly as a new academic discipline that would require new infrastructure, including whole new departments in universities, new journals to publish in, new Ph.D. programs to train more psychologists, and spread the budding science of psychology.

The growth of psychology occurred in tandem with the popularization of eugenics movements across the world, and the temporal overlap is more than just a coincidence. Eugenics required tests of human mental abilities to identify eugenically inferior people from eugenically superior people. Psychologists created the tests, and established whole domains of psychology, such as psychometrics, to measure individual differences in qualities of humans of interest to eugenics. Many psychologists were also proponents of eugenics. They wrote about their eugenics views in eugenics journals, and about their psychological research (that would be useful for eugenics) in psychology journals.

3.6.2 Leadership by eugenicists

I have not yet seen exhaustive historical research estimating how many psychologists were committed to the eugenics movements, in what capacity, for how long, and how their involvement differed across countries 5. Nevertheless, there are some clear clues in the historical record, especially for American psychology. Yakushko (2019) determined that 31 presidents of the American Psychological Association (APA) between 1892 and 1947 were affiliated with or leaders in eugenics societies. Eugenics affiliations are known from published documentation like membership lists in eugenics organizations.

My first thought when I read those numbers was: I wonder what the American Psychological Association conferences were like for over half a century, during the time when many of the presidents (elected by other psychologists) were publicly committed to the cause of eugenics? If similar proportions of academic psychologists at large were also proponents of eugenics like their leaders, what kinds of eugenic ideology was passed on to their students and to the general public as they taught about psychology? Did eugenic beliefs among psychologists influence the kinds of students they chose to admit into graduate schools? Did eugenic beliefs influence the kinds of research questions that psychologists asked? I think a total picture on these kinds of questions remains to be adequately answered by future research into the history of psychology.

Unfortunately, although it is clear that early psychology and psychologists were deeply involved in eugenics, it is not as clear that most modern institutions of psychology have widely acknowledged or reckoned with this history (but, see the work of the Association of Black Psychologists in chapter 4).

This section was written in the summer of 2021. Since that time there has been an acknowledgement by the APA (see addendum), and the APA awards have been renamed.

For example, psychological associations continue to name prestigious awards after famous psychologists who also played large roles in the eugenics movement. To name a few, the APA gives the E. L. Thorndike Career Achievement Award to recognize achievements in educational psychology; the Granville Stanley Hall Award for achievements in Developmental Psychology; and the Robert M. Yerkes Award for achievements in Military Psychology by non-psychologists. The Association for Psychological Sciences (APS) gives the James McKeen Cattell Fellow Award for contributions to applied research; and, the Society for Experimental Psychology gives the Howard Crosby Warren Medal for outstanding achievement in experimental psychology.

There are many ways to explore connections between psychology and eugenics. For example, the domains of clinical psychology, social psychology, developmental psychology, personality psychology, and others each have their own historical connections with the eugenics movement. We will explore a major connection in the next chapter on early intelligence testing that is relevant to broad topics in cognition.

3.6.3 Addendum: APA’s apology to People of Color

On October 29, 2021, the American Psychological Association council of representatives released a resolution titled, “Apology to People of Color for APA’s Role in Promoting, Perpetuating, and Failing to Challenge Racism, Racial Discrimination, and Human Hierarchy in U.S.”. The link to the statement can be viewed here: https://www.apa.org/about/policy/racism-apology.

This webpage contains additional links relevant to the content of this chapter, including a historical chronology examining psychology’s contributions to the belief in racial hierarchy and perpetuation of inequality of color in the U.S. The chronology can be viewed here: https://www.apa.org/about/apa/addressing-racism/historical-chronology

3.7 Additional Reading

For a longer reading list on eugenics visit: https://crumplab.com/blog/post_990_6_28_22_eugenicsbooks/

Kamin, L. J. (1974). The Science and Politics of IQ. Psychology Press.

Kühl, S. (2013). For the Betterment of the Race - The Rise and Fall of the International Movement for Eugenics and Racial Hygiene. Palgrave Macmillan.

An excellent resource establishing the scope and scale of eugenics movements across the world.

Selden, S. (1999). Inheriting Shame: The Story of Eugenics and Racism in America. Teachers College Press.

The Eugenics Archives. https://eugenicsarchive.ca/.

A deep and well organized web-based resource about the history of eugenics and its influences on society, with a Canadian focus.

The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. (2010). In A. Bashford & P. Levine (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195373141.001.0001

A comprehensive resource.

Tucker, W. H. (2002). The Funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund. University of Illinois Press.

Includes discussion of funding scientific racism within psychology.

Williams, R. (1974). A History of the Association of Black Psychologists: Early Formation and Development. Journal of Black Psychology, 1(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/gg3hq4

Wilson, R. A. (2017). The Eugenic Mind Project. MIT Press.

Yakushko, O. (2019). Eugenics and its evolution in the history of western psychology: A critical archival review. Psychotherapy and Politics International, 17. https://doi.org/10/gg3hsf

Yakushko, O. (2019). Scientific Pollyannaism: From Inquisition to Positive Psychology. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15982-5

Exemplary and highly informative works.

3.8 Appendix

3.8.1 References

Reuse

Citation

@incollection{crump2021,

author = {Crump, Matthew J. C.},

editor = {Crump, Matthew J. C.},

title = {Eugenics and {Psychology}},

booktitle = {Instances of Cognition: Questions, Methods, Findings,

Explanations, Applications, and Implications},

pages = {undefined},

date = {2021-09-01},

url = {https://crumplab.com/cognition/textbook},

langid = {en},

abstract = {This chapter describes the eugenics movement and some

connections to the larger discipline of psychology and research into

cognition. Some of these connections are expanded upon in later

chapters, including the next chapter on mental testing.}

}